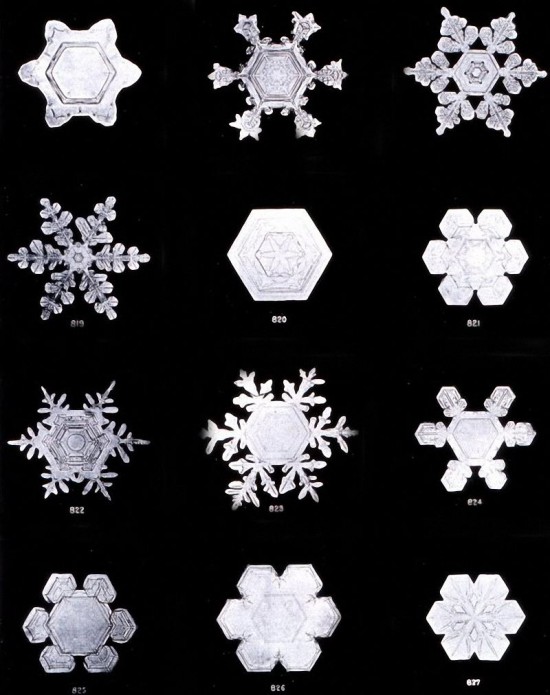

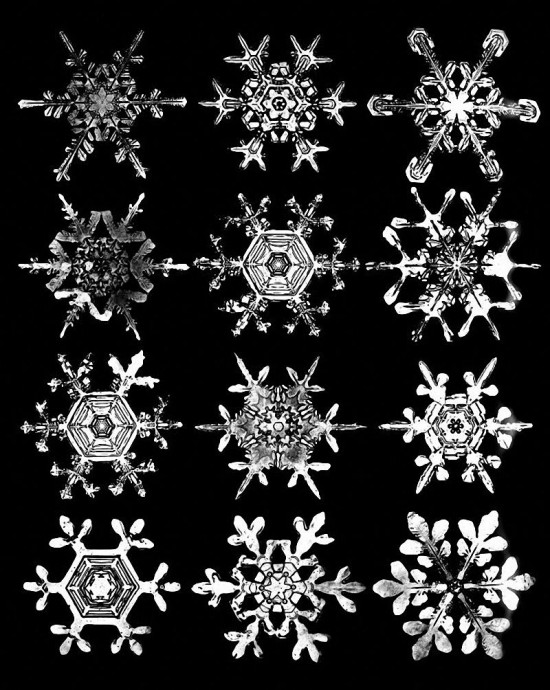

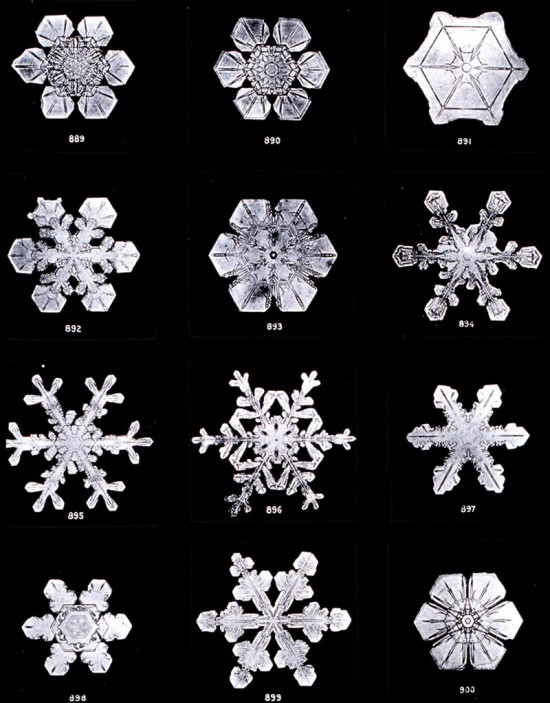

Young Wilson Alwyn Bentley became fascinated with snow crystals while living in his family’s farm. On the 15th of January, at the age of 20, he took the first picture of one by attaching a bellows camera to a microscope.

Over his lifetime he would capture over 5,000 such images, catching crystals on a blackboard and transferring them rapidly to a microscope slide. Even at bellow zero temperatures, snowflakes have very short lives as they quickly sublimate. In 1931 Bentley worked with William J. Humphreys and published Snow Crystals.

The various shapes and endless minute variations led the popular belief that no two snow crystals are the same

.

Yet still, snow crystals captured people’s imagination in a different manner; how could these intricate albeit very symmetric shapes come to be. How could the random creative process which gives birth to these intricate miniature variations produce such similarity across six directions within one snow crystal. D. McLachlan put the question: How does one branch of the crystal know what the other branches are doing during growth?

.

McLachlan’s explanation for the coordination of the growth among the six branches of a snow crystal is based on the existence of thermal and acoustical standing waves in the crystal.

From a beautiful passage in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain:

Indeed, the little soundless flakes were coming down more quickly as he stood. Hans Castorp put out his arm and let some of them to rest on his sleeve; he viewed them with the knowing eye of the nature-lover. They looked mere shapeless morsels; but he had more than once had their like under his good lens, and was aware of the exquisite precision of form displayed by these little jewels, insignia, orders, agraffes — no jeweller, however skilled, could do finer more minute work. Yes, he thought, there was a difference, after all, between this light, soft, white powder he trod with his skis, that weighed down the trees, and covered the open spaces, a difference between it and the sand on the beaches at home, to which he had likened it.

For this powder was not made of tiny grains of stone; but of myriads of tiniest drops of water which in freezing had darted together in symmetrical variation — parts, then, of the same inorganic substance which was the source of protoplasm, of plant life, of the human body. And among these myriads of enchanting little stars, in their hidden splendour that was too small for man’s naked eye to see, there was not one like unto another and endless inventiveness governed the development and unthinkable differentiation of one and the same basic scheme, the equilateral, equiangular hexagon. Yet each, in itself — this was the uncanny, the anti-organic, the life-denying character of them all — each of them was absolutely symmetrical, icily regular in form.

Yes, the real beauty of nature vis-à-vis a mechanical process is contained in irregularity and the non-repeating. Duplicates in nature inspire fear… and nature was never meant to be duplicated.

Mann continues:

They were far too regular for any substance meant to live. Indeed, the blood of life seemed to run cold at the mere suggestion of anything so precise. The secret of their precision was the secret of death, and Hans felt he understood the reason why the builders of antiquity were in the habit of purposely and furtively breaking, with minute deviation from symmetry, the rigid rule of their structure of columns.

Mad Scientist says,

Precious

on 04 December 2010 / 1:50 PM

Anthia Christodoulou Theofilou says,

Amazing nature. Excellent article! It really makes you wonder. Is anything coincidential?

on 19 February 2011 / 10:49 PM